Clojure + NumPy Interop: The 2026 Guide to Hybrid Machine Learning Pipelines

Why choose just one – JVM stability or NumPy’s speed- when it is actually possible to have both?

Using modern interop tools such as libpython‑clj, developers can integrate Clojure’s machine-learning capabilities with Python’s extensive ecosystem without incurring unnecessary overhead. Teams can now perform numerical computing in Clojure while leveraging the full power of NumPy’s C extensions for vectorization, broadcasting, and linear algebra.

When teams directly import NumPy arrays into the Clojure workflows, they get the best of both worlds: Clojure’s functional style and concurrency, plus NumPy’s raw performance. For teams developing AI software, this just makes sense. It is a smoother path to scalable, production-ready software solutions- without having to compromise.

The Interop Landscape

libpython‑clj: The Gold Standard

If developers want Clojure and Python to work together, libpython-clj sets the bar. They get direct access to NumPy, SciPy, and Scikit‑learn without extra layers or complications. Thanks to zero-copy memory mapping, data moves between the JVM and CPython without a hitch. Developers won’t waste time converting data in both directions.

Flexiana has strong expertise in connecting Clojure and Python for machine learning, and several detailed case studies demonstrate how libpython-clj enables teams to use major tools such as NumPy, SciPy, and scikit-learn in production environments. What stands out is how these examples show that developers do not have to choose between Python’s fast research ecosystem and Clojure’s rock-solid stability—they can leverage the strengths of both. This balanced approach helps teams build scalable, production-ready software solutions for real-world projects.

tech.ml.dataset: Clojure’s Pandas Alternative

If developers want to handle data directly in Clojure, tech.ml.dataset is the go-to option. It is the closest thing to Pandas on the JVM. The best part? It plugs straight into libpython-clj, allowing data transfer between the JVM and CPython without extra copies. Teams can use Clojure to prepare and manage their datasets before sending them to NumPy for intensive computational tasks.

Pandas vs. tech.ml.dataset

| Feature | Pandas (Python) | tech.ml.dataset (Clojure) |

| Columns | Flexible column types | Strongly typed columns |

| Indexing | Labels and multi‑indexing | Functional style indexing |

| Data Sharing | Needs serialization | Zero‑copy with libpython‑clj |

| Interop | Works inside Python only | Connects directly with NumPy |

Neanderthal: Native Clojure Numerics

Does it not require Python? Neanderthal is a powerhouse for numerical computing in Clojure. It is fast- built on BLAS and LAPACK, and if teams want GPU action, it connects to CUDA and OpenCL. Neanderthal needs direct GPU access without Python; it runs well in the JVM.

Comparison: NumPy vs. Clojure Native Numerics

| Feature | NumPy (Interop) | Neanderthal (Native) |

| Ecosystem | Python ML libraries (SciPy, scikit‑learn, PyTorch) | Focused on linear algebra, deep learning, and JVM tools |

| Performance | Very High — native BLAS/LAPACK via C extensions | Very High — native BLAS/LAPACK with JVM-native integration (no Python interop) |

| Ease of Use | Familiar to Python developers | Steeper learning curve for Clojure developers |

| Memory | Shared via libpython-clj | Native JVM/Off‑heap |

| GPU Support | CuPy/PyTorch interop | Built‑in CUDA/OpenCL |

| Integration | Works best in hybrid workflows | Best for JVM‑only projects |

| Community | Large Python community, many tutorials | Smaller but focused Clojure community |

| Deployment | Common in research and prototyping | Strong fit for production JVM systems |

| Flexibility | Wide range of ML libraries | Specialized for numerics and performance |

This table shows the trade‑offs clearly:

NumPy interop is a good choice if teams already work in Python and want access to its machine learning libraries. Neanderthal is better when teams need maximum speed, GPU acceleration, and want to stay fully inside the JVM.

Setting Up Clojure‑NumPy Environment

deps.edn Setup

To begin with, add libpython-clj to the deps.edn file. That is the bridge between Clojure machine learning and Python’s numerical stack.

Now, double-check where Python is installed on the system. Clojure requires a path to load libraries such as NumPy. Developers need to point to their Python interpreter or virtual environment.

REPL Integration

Once developers have configured the dependencies, they can import Python libraries directly into their REPL.

This quick example shows how developers can create a NumPy array and run a few operations, all from Clojure. It’s proof that NumPy interop works smoothly and that AI software development gets the ideal combination: Python’s speed with Clojure’s structure.

Zero‑Copy Magic

Here’s where things get really interesting. With tech.v3.dataset, you can move data between the JVM and CPython without making extra copies. This is called zero‑copy integration.

- No messing around with serialization, no wasted time.

- Just prepare your data in Clojure.

- Transfer it to NumPy for heavy numerical processing, then continue.

This setup makes Clojure a real contender for numerical computing. Developers are not merely connecting two languages. They are building scalable software solutions that can handle complex, real-world tasks.

Building a Hybrid ML Pipeline

Step ❶: Data Preparation

Use Clojure’s sequence functions for ETL. They make cleaning and shaping data pretty effortless.

- Just grab the map, filter, and reduce to process raw data.

- When developers need proper tables, add tech.ml.dataset into the combination.

- Continue using Clojure for data transformations until the data is ready for heavy numerical computation.

Step ❷: Numerical Crunching

Transfer the ready-made data to NumPy and let Python do the math.

- Vectorization runs operations across whole arrays.

- Broadcasting helps when arrays do not match in shape.

- Need matrix multiplication or decomposition? NumPy takes care of all the usual linear algebra work.

👉 Check out the NumPy official docs for more details.

Step ❸: Model Integration

Once the data is ready, load models from Scikit‑learn or PyTorch.

- Train or load them in Python as needed.

- For inference, use libpython‑clj to call Python directly from Clojure.

- Return results to the JVM for use in production or reporting processes.

Clojure maintains deployment stability, while Python’s ML ecosystem manages the models.

Why It Matters

The pipeline uses Clojure and Python, where they work best. Teams get:

- Clojure’s organized data processing.

- Python’s high-powered numerical computing.

- The JVM’s stability in the backend.

Developers can scale their software while leveraging the best features of both languages.

Benefits of the “Clojure + NumPy” Approach

✔️ REPL‑Driven Experimentation (Try Ideas Instantly)

Clojure’s REPL makes coding fast- write, change, and run code on the spot. That loop makes it easy to test ideas. In AI software development, where teams often need to experiment extensively, that speed makes a difference. Sharing snippets and testing together keeps work moving. It is simply a smoother way to work, especially when everyone is collaborating to solve tough problems.

✔️ Functional Integrity (Stay Functional and Clean)

Python’s math libraries often change developers’ data in place, which can lead to unexpected side effects. With Clojure for machine learning, they can integrate NumPy into a functional workflow. Their data remains predictable, functions do not modify the external state, and debugging becomes less painful. They spend less time chasing weird bugs or wondering why their output changed. What is the end result for teams working on numerical computing in Clojure? Code is clean, pipelines are stable, and growth is easier.

✔️ Enterprise Scaling with Clojure Concurrency (Scale Up Without Slowing Down)

On the JVM, Clojure manages heavy workloads with real concurrency. Combine with NumPy interop to speed up numerical computations, and teams get an environment that can handle huge datasets without slowing down. Flexiana has seen real drops in latency when they combine JVM concurrency with NumPy’s speed in their ML pipelines. It is not just about raw speed- this setup lets teams scale up confidently, with the assurance their system won’t fail when the load grows.

✔️ Balanced Strengths (Best of Both Worlds)

Clojure handles concurrency and orchestration. It also handles enterprise tasks. NumPy manages the math work. Together, they produce an accurate and efficient pipeline. Developers get both performance and stability, so they don’t have to choose. If the team needs to manage distributed workloads while handling heavy numeric processing, this approach works well. Tools like libpython-clj1 tie everything together, making integration feel seamless. It is a solid way to build hybrid systems that actually last.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Mismanaging Memory Between JVM and Python

Data coordination between Clojure and Python is challenging. If teams are not paying attention, they will end up copying large datasets multiple times, wasting memory and slowing everything down.

How to avoid it: Go for zero-copy integration whenever possible, using tools like libpython-clj1 or tech.ml.dataset. Do as much as teams can in Clojure, and only bring in NumPy when it is really needed for that speed. Always monitor memory usage when dealing with large arrays.

Overusing Interop Calls (performance hit)

Interop is great, but there is an overhead involved. When developers repeatedly call Python functions from Clojure in a tight loop- thousands of times- performance drops drastically.

How to avoid it: Batch the work. Push large chunks of data to NumPy and allow it to process the calculations. Keep the control flow in Clojure and cut down on all those frequent back-and-forth calls.

Ignoring Concurrency Design

Clojure runs on the JVM, which indicates it is built for concurrency. But if teams forget to design for it, workloads jam up. Python’s GIL limits running things in parallel on the Python side.

How to avoid it: To handle concurrent processes, rely on Clojure’s concurrency tools- atoms, refs, agents, and futures. Let Python focus on numerical computation, while Clojure runs the show and scales things up. It helps to avoid running into the GIL’s roadblocks.

Not Testing Startup/Deployment Properly

Interop setups tend to fail when a developer moves from the laptops to production- wrong paths, missing dependencies, corrupted environments. On-site equipment might suddenly fail at other locations.

How to avoid it: Test the startup scripts. Ensure the Python interpreter is configured correctly, with automated CI/CD checks to quickly identify issues.

Driving Results Through Engineering Excellence

Speed of Development

Clojure brings everything together smoothly. It consolidates the entire pipeline into one place without creating confusion. Developers can connect Python libraries, JVM tools, and their own logic pretty fast- no mountains of boilerplate, just straight to the real problems. And with the REPL, Developers are not stuck waiting for long builds. Quick adjustments and tests keep projects on track.

Maintainability

Clojure sticks to a functional style, so the code stays clean, and the data flows in a way that actually makes sense. Side effects remain under control. When your pipeline gets bigger, you spot bugs early, and resolving them doesn’t become a hassle. New people can jump in and understand what’s happening without getting confused, which makes onboarding much easier. Bottom line: fewer nasty surprises, easier upkeep.

Long‑Term Stability

The JVM has been around forever, and people trust it. Years of tweaking, monitoring, and deploying mean it just works. NumPy runs efficiently, so systems scale up and handle heavy loads with ease. It remains fast and stable as workloads increase.

Team Collaboration

The REPL makes small changes easy to test. Fast result sharing keeps everyone in sync. Teams scale with ease thanks to clear feedback that shows changes.

Integration Flexibility

Clojure connects easily to Python, Java, and JVM tools. It plays nicely with the enterprise tools that teams already have, and they still get access to Python’s whole ML world. Teams arenot required to choose sides- they can use what works best from both. They get the freedom to bring in new tools without breaking what is already working.

❓ Quick Answers to Common Questions

Performance and Reliability

Q1: Does libpython‑clj make code slow?

Not really. The primary slowdown stems from repeatedly switching between Clojure and Python. For heavy numerical stuff, that extra cost barely matters compared to how fast NumPy runs.

Q2: Can I use this in production?

Absolutely. Real-world teams rely on it for JVM reliability and Python’s ML strength. Test startup and deployment the same way you test other tools.

Q3: How is memory usage?

Both the JVM and Python consume resources. Pay attention to memory, especially if you’re working with huge datasets.

Q4: Is libpython-clj still maintained?

Indeed. The Clojure community ensures compatibility with the latest versions of Python and keeps it up to date.

Concurrency and Scaling

Q1: What about the Python GIL?

Python code still runs under the Global Interpreter Lock. Clojure handles concurrency separately, so workloads scale, whereas Python handles concurrency internally.

Q2: Does it support parallel workloads?

Yes. Clojure gives you concurrency tools like atoms, refs, agents, and futures, all running on the JVM, which is built for scale. Python handles numerical processing.

Integration and Flexibility

Q1: Does it support GPU acceleration?

While Python libraries such as TensorFlow, PyTorch, and CuPy support GPU acceleration, libpython-clj itself is only an interop layer and neither enables nor restricts GPU usage.

Q2: Is it compatible with virtual environments?

Yes. Set libpython-clj to your Python virtual environment to keep dependencies simple.

Q3: Can I mix and match multiple Python libraries?

Yes. Import and use any Python library you want, just like you would in Python. Clojure ties everything together.

Developer Experience

Q1: How difficult is debugging?

Quite simple. Errors show up directly in Clojure, and the REPL makes it easy to try code in small steps.

Q2:Does the REPL help collaboration?

Definitely. The REPL makes quick tests easy, and results are simple to share.

Shaping the Future of Hybrid ML

Trends in Hybrid ML Pipelines.

Hybrid ML pipelines are gaining popularity quickly. Teams want the dependable stability from the JVM, but they are not willing to give up Python’s powerhouse ML libraries. So, rather than choosing one, an increasing number of projects use both. Combining them makes it way easier to scale up, keep things running smoothly, and adjust quickly as the workload changes.

Growing Role of Interop Tools Like libpython‑clj1.

Interop tools like libpython-clj1 are no longer just for experimentation. These days, libpython-clj1 is the go-to for integrating Clojure and Python in real production code. Developers can import NumPy, SciPy, or Scikit-learn right from Clojure- no awkward workarounds. As more teams join, tools like this are becoming the backbone of hybrid pipelines.

Potential Improvements in Zero‑Copy Integration.

Zero-copy integration is already a game-changer. Eliminating data duplication saves time and memory. Looking ahead, there is room to further improve it. Think faster pipelines, better support for huge datasets, smoother GPU acceleration, and handling complicated data structures without the usual headaches. All this will further reduce overhead and make everything feel almost effortless.

Where Flexiana Sees Hybrid ML Heading in 2026 and Beyond.

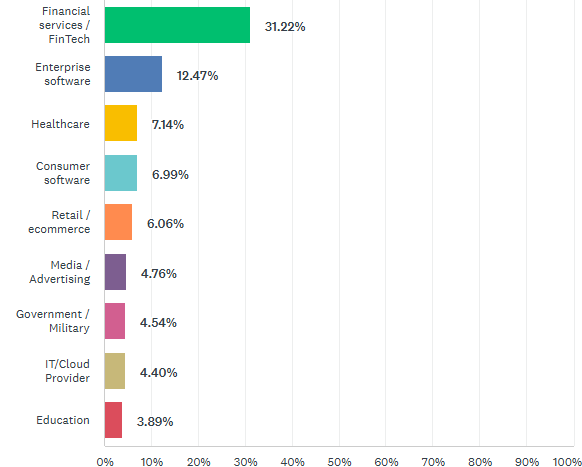

At Flexiana, we have seen hybrid ML pipelines move out of the “experimental” corner and take center stage for big companies. Here is where things are headed by 2026 and beyond:

- Teams will see hybrid ML everywhere- finance, healthcare, retail, and more.

- Cloud-native integration will become more integrated.

- Teams will prioritize maintainability and stability over short-term speed.

- Hybrid setups will be the default, not just a backup plan.

The direction is clear: Hybrid ML pipelines are not a passing trend. They are the new normal, enabling developers to leverage the best tools from both worlds and get things done.

Final Thoughts

Clojure machine learning brings the rock-solid reliability of the JVM, while NumPy offers that raw speed Python’s known for to process numerical data. Combine them, and developers get a hybrid ML pipeline that does not force them to choose between stability and performance. With tools like libpython-clj1, moving data between the two just works. Team can access enterprise-level concurrency and fast numerical work at the same time- no compromises, especially if teams are pushing the limits of numerical computing in Clojure.

Bringing these strengths together enables teams to move faster in AI software development, test new ideas without getting stuck, and keep their codebase clean and scalable as their needs grow. It is a practical setup- flexible, efficient, and ready to handle whatever real-world demands come their way.

If you are ready to kick off your own hybrid ML pipeline, Flexiana can help you blend JVM reliability with NumPy speed. Let’s get started.

The post Clojure + NumPy Interop: The 2026 Guide to Hybrid Machine Learning Pipelines appeared first on Flexiana.