This article describes how to build a web service based on Clojure and the Duct framework. It covers all the necessary details of every part of Duct needed for this task. On completion, the reader should be able to write a web service from scratch with tests, configurations, and components calling 3rd party services.

The article is for intermediate programmers with a basic knowledge of web services and Clojure.

Clojure is a really different programming language compared to conventional languages like Java, Kotlin, Javascript, or functional languages like F#. The very first thing that everybody spots are its parenthesized prefix notation. The notation may look odd, but it has a lot of advantages compared to C-like syntax:

- Compact syntax

- Simple syntax parser and highlighter

- No priority of operators struggle

- No breaking changes for new versions, due to new keyword/core function

- Easy to read any code, everything is a function

The second special thing about Clojure’s environment is that there is no standard framework like Django, Ruby On Rails, Spring in other languages. Clojure lets a programmer compose a framework from small libraries. I guess that this decision is based on the idea that there is no one hammer for all problems. This comes with a lot of consequences.

Pros

- A perfectly tailored framework to fit the problem.

- No limitation to replace marshalling, HTTP, DB, routing and other libraries.

- No overweight framework, only the parts used are in a project.

- Great for microservices.

Cons

- Hard at the beginning, experience with libraries needed.

- Very hard for beginners without architecture skills.

- Boilerplate code.

- No scaffolding (like in Ruby On Rails)

This post is about Duct. The framework is light and composed from other (well-known in the Clojure world) small libraries (as is almost everything in Clojure). These are the main parts that are covered by Duct:

- Configuration – local, production env., env. variables, …

- HTTP handler with an application server

- Database layer – a connection poll

- Prepared middlewares for common security, HTTP headers, Content negotiation, …

- Logging

- Error handling

- REPL – a code hot-swap

Architecture

The code

Let’s create a new project where we can see how to do general stuff with Duct. We are going to create a service for sending SMS messages.

We start by creating a project structure from Leiningen template by calling:

lein new duct sms +api +examplern[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana]$ lein new duct sms +api +examplernGenerating a new Duct project named sms...rnRun 'lein duct setup' in the project directory to create local config files.rn[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana]$

Let’s describe the command and what was created:

- lein new generates a new Clojure project with Leiningen template

- duct is a name of a template

- sms is a name of a new project

- +api is an option that adds middleware for APIs

- +example is an option that adds some example code

You can find more options in Duct’s README file https://github.com/duct-framework/duct#quick-start

Leiningen created a folder called sms. As we can see in the result above, the command

will create configuration files for a local development and these files should not be watched by a version control system. The command prints out what files have been created:

[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana/sms]$ lein duct setuprnCreated profiles.cljrnCreated .dir-locals.elrnCreated dev/resources/local.ednrnCreated dev/src/local.cljrn[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana/sms]$

The template also generates the .gitignore file so you don’t have to alter the file manually.

The project structure

Leiningen generated a project from a template, let’s describe a project structure.

- README.md: This is the obvious one, this file describes a project, contains installation and other useful notes.

- dev: This folder contains files only for development mode. These files will not be part of a production JAR. It contains a configuration for the development and local environment (dev/resources/local.edn)

- profiles.clj: Allows to override profiles.

- project.clj: This is an important one. It contains project dependencies and plugins, build profiles, etc.

- resources: contains static files like: project configuration, images, Javascripts, CSS, SQL, etc. These files will be a part of the production JAR.

- src: contains all files that would be compiled: clj, cljc, cljs, cljx or java files

- test: All the tests. These files will not be part of the production JAR.

We should be able to run the project as it is right now, because we passed +example option when we were generating the project. Let’s check it if it’s working. We can start the REPL as usual (lein repl), load a development profile (call (dev) in the repl) and start the server (we can call (go) or (reset)). Both of these functions start the server, in the following steps we will use reset, because it refreshes the code and restarts the server.

If everything went well, the output should be almost the same. The interesting information in the output is that the server started on port 3000 (we can change this in resources/sms/config.edn). The leiningen’s template created the example handler, so we can hit this URL http://localhost:3000/example.

As we can see, it works.

The routes

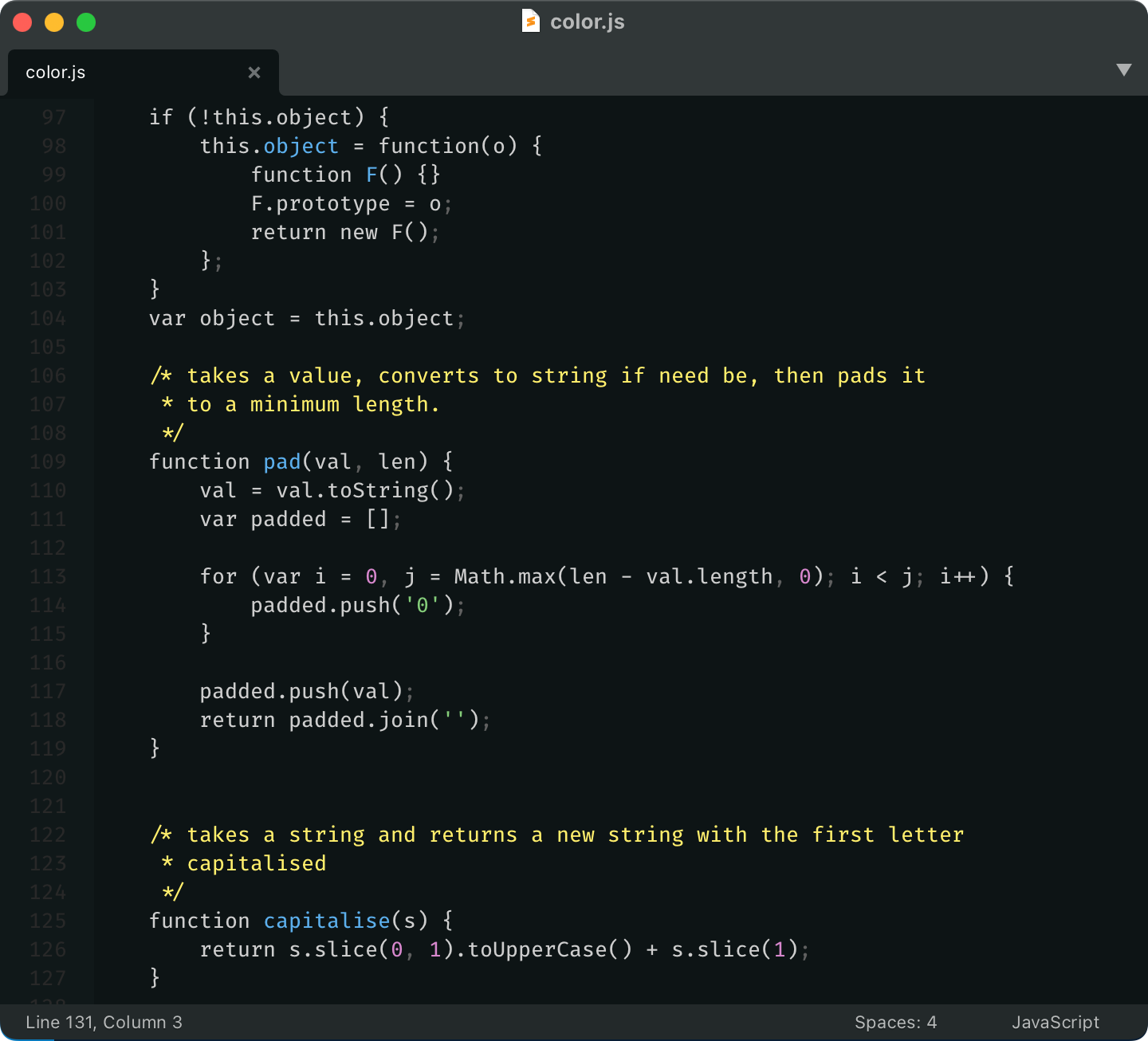

By default the project template generates routes to <project-name>.handler/example. This is just a convention, technically you can put the routes anywhere you want. Our example route is in sms.handler.example namespace, when you open a file you should see something like:

The code is pretty small, but there are a few new things. Let’s describe them.

First, there is an Integrant component defined by defmethod ig/init-key. Integrant is a micro-framework that allows you to create components and their configuration, and compose them together (you can think about it as a small DI framework). A component has a life-cycle, but for now init-key would be enough for us. As we can see from its name, init-key is called when the component is being initialized. The name of the component is a namespaced keyword :sms.handler/example and it should follow the code namespace. Integrant tries to load both variants of namespaces: sms.handler.example and sms.handler you can find more about it in the documentation. The last thing for the component is its configuration/options (this is a Clojure map, it could contain other components), but this is not important for now.

Second thing is the route itself. The route is defined by the Compojure library. The usage of the library is pretty simple and probably the simplest for beginners. The route is defined by the macros context and GET. Both macros are imported from compojure.core namespace (A side note :using :all is probably not a good idea, it’s hard to say if a function is from the same namespace, imported by :refer or :all, see more).

The Context macro allows you to wrap more routes with the same prefix to remove a path redundancy. The GET macro simply takes a path segment to match (in our example just /example), a parameters vector (we take none currently), and a response body or function. The response must be a valid Ring response (the simplest example is a map with :body and :status keys).

Now we know how the routes are defined, but how does the framework know that there are any routes? Let’s open the project’s configuration resources/sms/config.edn.

As we said above :sms.handler/example is the route component. As you can see the component takes a Clojure map. We can pass another dependency to the component by referencing it (e.g. #ig/ref :duct.database/sql). #ig/ref is syntax sugar for referencing other components. In case you are curious about the details see the EDN documentation. If you want to see more details about it you can check the repository, but in short, it uses Hikari Connection Pool. We will not use a database in this article, so let’s move on.

On line 4 we can see a configuration for :duct.router/cascading, this component is a default router from the template and it takes a vector of references to other components. These components are route components. So the router component handles a connection between a request (Ring object) and the router itself.

The API

In the previous chapter, we described routes and their configuration. Let’s do some real work and add a resource for creating messages. Our resource handler will accept a message with the following keys:

- receiver: a phone number as a String

- text: a message text as a String

Let’s start with renaming the namespace sms.handler.example to sms.handler.api. We also need to rename the :sms.handler/example component in config.edn and remove the test namespace sms.handler.example-test. You can directly remove the namespace file because we will cover it later.

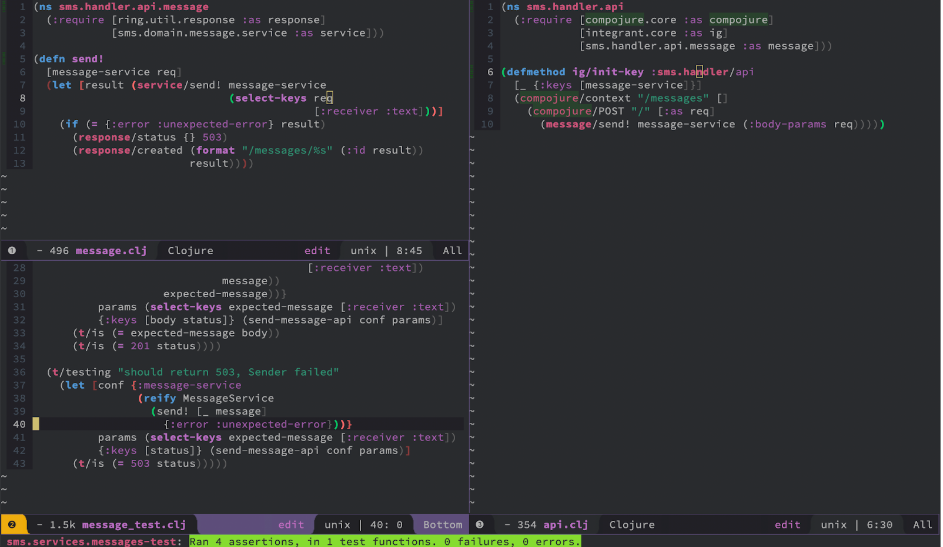

The handler file should be like:

(ns sms.handler.api

(:require [compojure.core :refer compojure]

[integrant.core :as ig]))

(defmethod ig/init-key :sms.handler/api [_ options]

(compojure/context "/messages" []

(compojure/GET "/" []

{:body {:example "data"}})))

The configuration file should be like:

{:duct.profile/base

{:duct.core/project-ns sms

:duct.router/cascading

[#ig/ref [:sms.handler/api]]

:sms.handler/api

{:db #ig/ref :duct.database/sql}}

:duct.profile/dev #duct/include "dev"

:duct.profile/local #duct/include "local"

:duct.profile/prod {}

:duct.module/logging {}

:duct.module.web/api

{}

:duct.module/sql

{}}

We can test the changes by calling curl http://localhost:3000/messages. If you have already started the REPL, you need to refresh the code in the JVM by calling (reset) from the REPL. Otherwise, it should work when you start the server.

The resource handler would accept a message with keys (receiver, text) and return the same message with the new key id (as String). Sending a message is not an idempotent process so we also need to change the HTTP method to post.

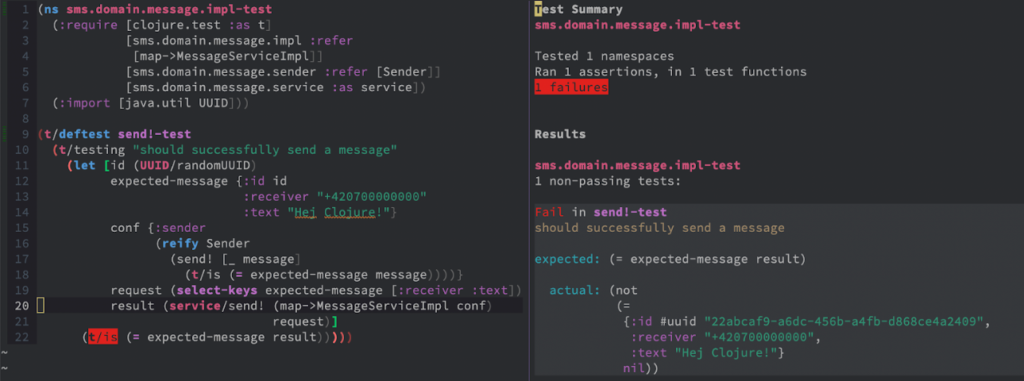

Let’s use TDD and start with defining the test. Create a file sms.domain.message.impl_test.clj with these contents:

(ns sms.domain.message.impl-test

(:require [clojure.test :as t]

[sms.domain.message.impl :refer

[map->MessageServiceImpl]]

[sms.domain.message.sender :refer [Sender]]

[sms.domain.message.service :as service])

(:import [java.util UUID]))

(t/deftest send!-test

(t/testing "should successfully send a message"

(let [id (UUID/randomUUID)

expected-message {:id id

:receiver "+420700000000"

:text "Hej Clojure!"}

conf {:sender

(reify Sender

(send! [_ message]

(t/is (= expected-message message))))}

request (select-keys expected-message [:receiver :text])

result (service/send! (map->MessageServiceImpl conf)

request)]

(t/is (= expected-message result)))))

To be able to compile a test we need to also define the protocols and the implementation file. Let’s define sms.domain.message.sender namespace like:

(ns sms.domain.message.sender)

(defprotocol Sender

(send! [this message]))

And the service itself sms.domain.message.service:

(ns sms.domain.message.service)

(defprotocol MessageService

(send! [this message]))

And the implementation namespace sms.domain.message.impl:

(ns sms.domain.message.impl

(:require [sms.domain.message.service :refer [MessageService]]))

(defrecord MessageServiceImpl []

MessageService

(send! [_ message]))

We did several things here. Let’s describe them to make them clear. First, we created a domain folder with a message subfolder. By that step, we made an explicit sign that the domain folder only contains our domain logic. A message is a domain object so everything related to it should be placed in sms.domain.message namespace. This structure increases the code cohesion because the functions that operate on the same data structures are together [BobCC]. When we would like to add another domain model, we just add another namespace or subfolder to the domain folder. Everybody who looks into the domain folder will see what the domain objects are, and where the functions that operate on them are.

We created a MessageSender protocol to separate behavior from implementation. The protocol provides several benefits:

- The domain behavior is not tightly coupled with the sender’s implementation.

- The protocol provides an explicit boundary between the domain logic and the rest of the system.

- It’s easy to test domain objects and their behavior.

- It’s possible to replace a sender at runtime.

Now we should be able to run tests via REPL by calling (test) or from your editor or IDE. Don’t forget to (reset) the code after every change when you run the tests from the REPL. In one of our previous articles, we described how to work with REPL.

No matter how you call the tests, they should fail and the output should look like this:

And that’s good! Because we see that our code works and it fails in the expected state. As you can see the results says that a message map was expected but the function returned nil.

Now we can implement the resource handler of course we will not be implementing real message sending. Rather we would delegate sending messages to the Sender protocol, but before that we need to talk about boundaries.

Boundaries

When a system is being designed it’s a good practice to put the domain logic into the core of the system (ideally as pure functions) and move all communication with the outside world to the edges or boundaries of that system [BobCC]. This design approach has many advantages:

- It makes explicit what is a part of the core and what is not.

- It allows us to test the system components independently.

- These boundaries can be replaced at runtime.

- It allows us to develop the system even if we don’t know the boundary’s details.

- This separation is done on the architecture and structure layer (project’s layout, files, …) of the system.

This may sound too abstract or theoretical, so let’s show it in an example. The Sender protocol defines a boundary. This boundary is shaped at the core of the system. But its implementation is shifted outside of the core of the system. E.g. an implementation could be placed in sms.boundaries.gateway namespace.

Another example of a boundary is the repository pattern [FowlerPEAA]. The repository provides a collection-like interface for accessing domain objects. Its implementation typically connects to a database.

The Sender with one method send! takes a configuration and message for sending. Now we can continue with implementing the system even if we don’t know the real API for sending messages.

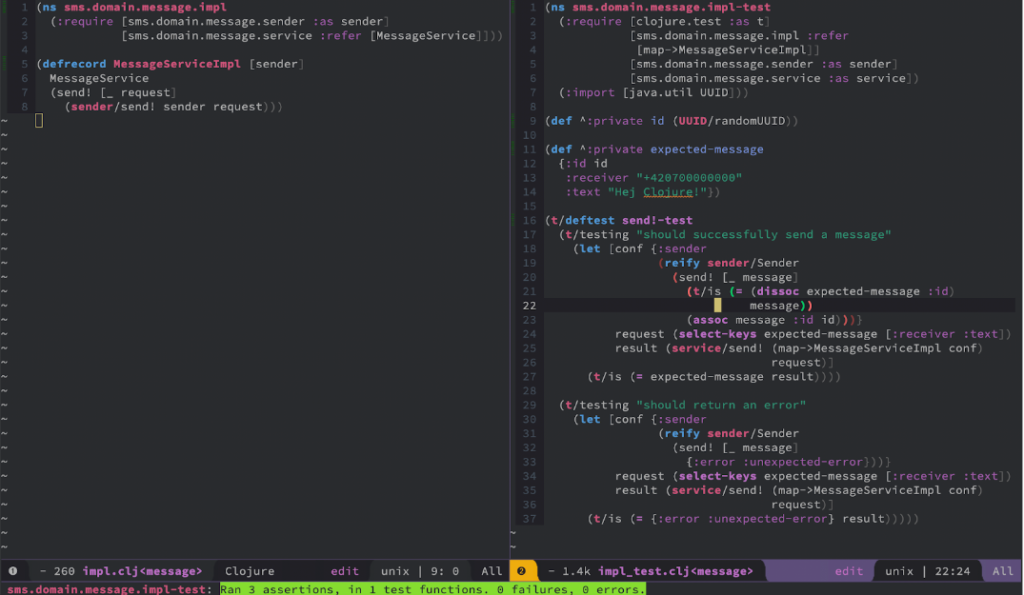

Now we can define the expected Sender behavior in the test. The Only thing we know is that the API returns an ID of a sent message and we want to add this ID to the message and return it to the caller. In case of an error, it would return an error result. The updated test could look like this:

(ns sms.domain.message.impl-test

(:require [clojure.test :as t]

[sms.domain.message.impl :refer

[map->MessageServiceImpl]]

[sms.domain.message.sender :as sender]

[sms.domain.message.service :as service])

(:import [java.util UUID]))

(def ^:private id (UUID/randomUUID))

(def ^:private expected-message

{:id id

:receiver "+420700000000"

:text "Hej Clojure!"})

(t/deftest send!-test

(t/testing "should successfully send a message"

(let [conf {:sender

(reify sender/Sender

(send! [_ message]

(t/is (= (dissoc expected-message :id)

message))

(assoc message :id id)))}

request (select-keys expected-message [:receiver :text])

result (service/send! (map->MessageServiceImpl conf)

request)]

(t/is (= expected-message result))))

(t/testing "should return an error"

(let [conf {:sender

(reify sender/Sender

(send! [_ message]

{:error :unexpected-error}))}

request (select-keys expected-message [:receiver :text])

result (service/send! (map->MessageServiceImpl conf)

request)]

(t/is (= {:error :unexpected-error} result)))))

We have defined the configuration for the API component with a boundary Sender. Actually we have reified the protocol (an anonymous implementation) in place just to simulate a response from the service and also a given message is asserted to the expected one (line 18).

If we run the tests again, nothing would change! Because we haven’t changed the handler’s implementation. So let’s update the implementation to use the Sender’s function send!.

(ns sms.domain.message.impl

(:require [sms.domain.message.sender :as sender]

[sms.domain.message.service :refer [MessageService]]))

(defrecord MessageServiceImpl [sender]

MessageService

(send! [_ request]

(sender/send! sender request)))

There are a few new things. First, the function uses the Sender’s send! function. Second, a sender field was added to MessageServiceImpl record.

If we run the tests now they should work.

Now we have finished the domain logic. The architecture may look too complicated for that simple task. But real systems are more complex and too complicated for the presentation.

Handling the HTTP requests

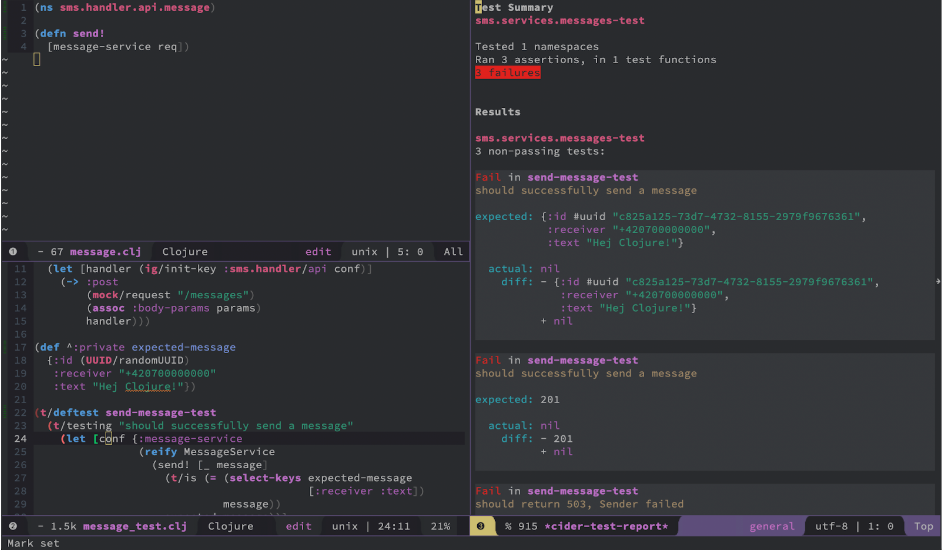

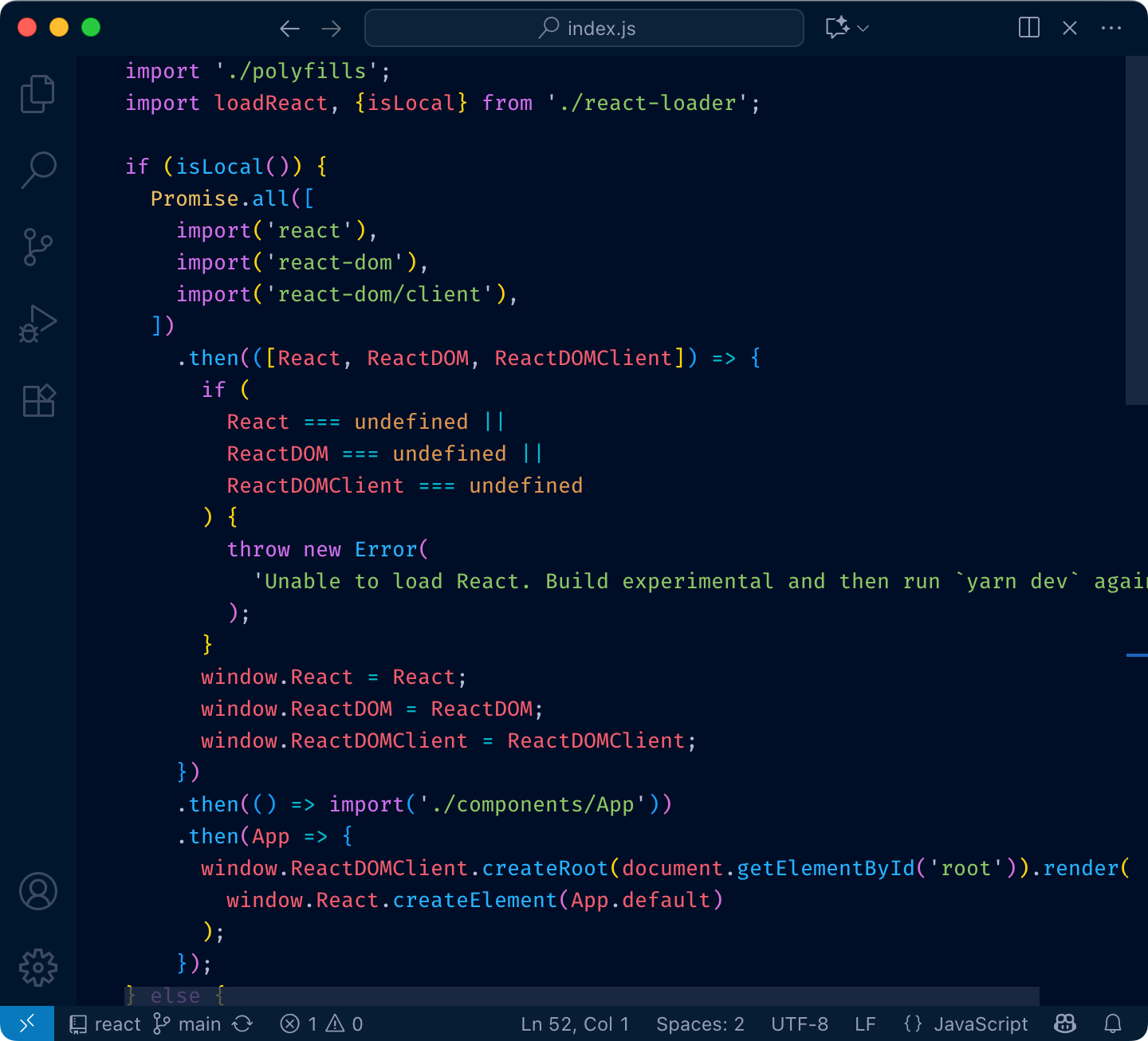

At this point, we have implemented the domain logic, but we don’t have any entry points to access the code. We are going to create an HTTP handler (or you can call it a controller). As in the previous section, we start with tests.

The test may look like this:

(ns sms.services.messages-test

(:require [clojure.test :as t]

[integrant.core :as ig]

[ring.mock.request :as mock]

[sms.domain.message.service :refer [MessageService]]

[sms.handler.api])

(:import [java.util UUID]))

(defn- send-message-api

[conf params]

(let [handler (ig/init-key :sms.handler/api conf)]

(-> :post

(mock/request "/messages")

(assoc :body-params params)

handler)))

(def ^:private expected-message

{:id (UUID/randomUUID)

:receiver "+420700000000"

:text "Hej Clojure!"})

(t/deftest send-message-test

(t/testing "should successfully send a message"

(let [conf {:message-service

(reify MessageService

(send! [_ message]

(t/is (= (select-keys expected-message

[:receiver :text])

message))

expected-message))}

params (select-keys expected-message [:receiver :text])

{:keys [body status]} (send-message-api conf params)]

(t/is (= expected-message body))

(t/is (= 201 status))))

(t/testing "should return 503, Sender failed"

(let [conf {:message-service

(reify MessageService

(send! [_ message]

{:error :unexpected-error}))}

params (select-keys expected-message [:receiver :text])

{:keys [status]} (send-message-api conf params)]

(t/is (= 503 status)))))

Let’s also add the handler function, then we can compile the code:

(ns sms.handler.api.message)

(defn send! [message-service req])

When we run the tests, they should fail.

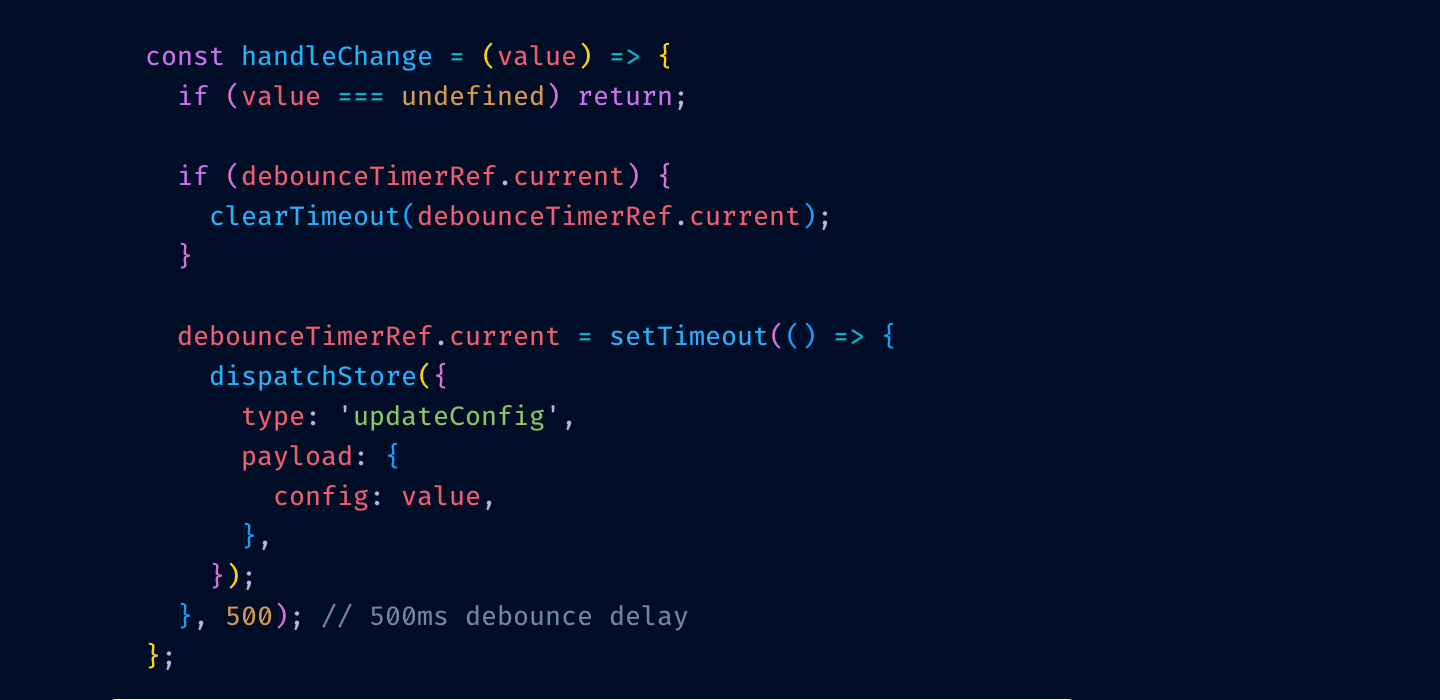

We should probably describe the test file and some of its interesting parts. We have defined the send-message-api function that wraps the API call. It calls ig/init-key on the API components with some configuration (the same thing happens when the application’s server starts), the application calls a post request with the given params.

The test itself is pretty simple, we have defined the component’s configuration as conf with one key called message-service. Under that key, we reified (mocked) the service protocol to expected behavior. We have made actual calls of the API and assert the result (body and status in this case).

The second test is almost the same as the first one, except the service returns an error result.

The very simple implementation of the handler may look like:

(ns sms.handler.api.message

(:require [ring.util.response :as response]

[sms.domain.message.service :as service]))

(defn send! [message-service req]

(let [result (service/send! message-service

(select-keys req

[:receiver :text]))]

(if (= {:error :unexpected-error} result)

(response/status {} 503)

(response/created (format "/messages/%s" (:id result))

result))))

Now tests should be green.

Production implementation

Well, we have implemented the HTTP handler and also added tests. But if we call the handler e.g. via curl

curl localhost:3000/messages -X POST -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"receiver": "+4207000000000", "text": "Hej Clojure!"}'

We would get something like this:

java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: No implementation of method: :send! of protocol: #'sms.domain.message.service/MessageService found for class: nil

The Message Service needs production implementation. Don’t be afraid we are not going to implement a real SMS sender. Instead, we will forward the message to another service via HTTP. First, let’s add a new dependency to the project HTTP-Kit, the latest stable version is 2.3.0. Update project.clj and restart the REPL, yes this is really needed. Start the REPL and create a file src/sms/boundaries/sms_gateway.clj with the following content:

(ns sms.boundaries.sms-gateway

(:require [duct.logger :as logger]

[integrant.core :as ig]

[jsonista.core :as jsonista]

[org.httpkit.client :as http]

[sms.domain.message.sender :refer [Sender]]))

(def mime-type "application/json")

(def default-headers

{"Accept" mime-type

"Content-Type" mime-type})

(defrecord SmsGateway [logger url]

Sender

(send! [_ message]

(let [{:keys [body status] :as response}

(http/post url

{:as :text

:body (jsonista/write-value-as-string message)

:headers default-headers})]

(case status

(200 201) (jsonista/read-value body)

(do

(logger/log logger :error response)

{:error :unexpected-error})))))

(defmethod ig/init-key :sms.boundaries/sms-gateway

[_ opts]

(map->SmsGateway opts))

On line 14 the Sender protocol is implemented. The record takes a logger instance and a url of the remote service. An implementation of send! The method is pretty straightforward, the API is called and if a response is successful (HTTP code 200 or 201) the response is parsed, otherwise, the response is logged and :error is returned. On line 27 the Integrant component is defined. The component converts a given configuration to a new record Sms Gateway.

Now we have a component for the Sender, but we also need a component for MessageService to be able to pass the Sender’s implementation. Let’s create a file sms.services.message with the following content:

(ns sms.services.message

(:require [integrant.core :as ig]

[sms.domain.message.impl :refer

[map->MessageServiceImpl]]))

(defmethod ig/init-key ::service

[_ opts]

(map->MessageServiceImpl opts))

The code is very simple. The Integrant component just creates an implementation of MessageService.

Let’s initialize the component in the project’s configuration. Let’s update resources/sms/config.edn like this:

{:duct.profile/base

{:duct.core/project-ns sms

:duct.router/cascading

[#ig/ref [:sms.handler/api]]

:sms.boundaries/sms-gateway

{:logger #ig/ref :duct/logger

:url #duct/env ["SMS_GATEWAY_URL" Str]}

:sms.services.message/service

{:sender #ig/ref :sms.boundaries/sms-gateway}

:sms.handler/api

{:message-service #ig/ref :sms.services.message/service}}

:duct.profile/dev #duct/include "dev"

:duct.profile/local #duct/include "local"

:duct.profile/prod {}

:duct.module/logging {}

:duct.module.web/api

{}

:duct.module/sql

{}}

On line 7 the SmsGateway component is initialized with the Duct’s logger and the SMS Gateway URL that is taken from an environment variable called SMS_GATEWAY_URL (as String). On line 11 the MessageService component is initialized with a sender.

This usage of Inversion of Control allows us to easily change the Sender’s implementation in tests, when the system starts, and even at runtime.

Unfortunately in local development we probably aren’t able to connect to the real SMS Gateway. But fortunately, we can fix this problem by creating a mock of the gateway. Let’s create a silly mock of the gateway dev/src/sms_dev/boundaries/sms_gateway_mock.clj

(ns sms-dev.boundaries.sms-gateway-mock

(:require [integrant.core :as ig]

[sms.domain.message.sender :refer [Sender]])

(:import [java.util UUID]))

(defrecord SmsGatewayMock []

Sender

(send! [_ message]

(assoc message :id (UUID/randomUUID))))

(defmethod ig/init-key :sms-dev.boundaries/sms-gateway-mock

[_ opts]

(map->SmsGatewayMock opts))

As you can see the silly implementation of Sender protocol just put an id on a given message to simulate the real behavior.

Now we have to tell the Duct to use SmsGatewayMock just for local development. Update dev/resources/local.edn file:

{:sms-dev.boundaries/sms-gateway-mock {}

:sms.services.message/service

{:sender #ig/ref :sms-dev.boundaries/sms-gateway-mock}}

On the very first line, a SmsGatewayMock is created and on another line, we tell the :sms.services.message/service to use the SmsGatewayMock as a Sender.

Now if we restart the REPL or call (reset) in the REPL, the code will be refreshed and we should be able to call the API e.g. via curl:

curl localhost:3000/messages -X POST -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -d '{"receiver": "+4207000000000", "text": "Hej Clojure!"}'

If everything went well the output will look like this:

{"receiver":"+4207000000000","text":"Hej Clojure!","id":"097bd803-c3fb-4d4a-beeb-bc381ec4e4d8"}

As you can see we have sent the message and a new id has been put into that message. Because we added the SmsGatewayMock to the dev folder the mock will not be part of the production JAR (all files from the dev folder will not be included too).

Secret magic

You may be wondering how is it possible that a request’s body was parsed to a map. There is one important thing we haven’t described yet. The Duct has got modules with default configurations for common middlewares like Ring defaults. The module is named :duct.module.web/api and it’s initialized in the project’s configuration. If you’re curious you can check the internals and see that it uses Muuntaja for marshalling.

The module puts middleware around :duct.core/handler (the main handler called from the HTTP servlet) when the system starts. This is default behaviour and it can be overridden, but we don’t want to go so far in this article.

When the Muuntaja middleware sees Content-Type in a request’s headers it can try to negotiate and parse the request (in our case to a map). If a request doesn’t have any known Content-Type, the attribute :body-params on the request object will be nil.

As you can see now technically there is no hidden magic, but a beginner could be surprised or confused.

Production

We have implemented the web service and now we want to run it in a staging or production environment. We need to have a stand-alone file that can be run with JDK. Let’s run the following command: lein uberjar

[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana/sms]$ lein uberjar

Compiling sms.boundaries.sms-gateway

Compiling sms.domain.message.impl

Compiling sms.domain.message.sender

Compiling sms.domain.message.service

Compiling sms.handler.api

Compiling sms.handler.api.message

Compiling sms.main

Compiling sms.services.message

Created /Users/lukas/dev/flexiana/sms/target/sms-0.1.0-SNAPSHOT.jar

Created /Users/lukas/dev/flexiana/sms/target/sms-0.1.0-SNAPSHOT-standalone.jar

Now we can take the sms-0.1.0-SNAPSHOT-standalone.jar and run it everywhere, where JDK is installed.

You can simply test it from a command line. Before running it the Gateway URL must be set via an environment variable. Let’s try it:

[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana/sms]$ export SMS_GATEWAY_URL="http://localhost:8080/smsgateway"

[lukas@hel:~/dev/flexiana/sms]$ java -jar target/sms-0.1.0-SNAPSHOT-standalone.jar

20-05-25 10:28:01 hel REPORT [duct.server.http.jetty:13] - :duct.server.http.jetty/starting-server {:port 3000}

As you can we have set the SMS_GATEWAY_URL variable and run the application. In the command line, we can see that the application has started on port 3000. So if the gateway service was running on port 8080 we would be able to test it by posting a message to http://localhost:3000/messages.

Duct uses by default Timbre for logging. In the development profile, all logs go to logs/dev.log file. But in the production, all logs are sent to stdout.

Conclusion

This article has introduced a Clojure framework, Duct, that helps programmers with building server-side applications. The Duct parts have been briefly described with the necessary details. All the described Duct’s parts have been presented with practical examples and tests.

A reader should be able to create a new server-side application, implement HTTP handlers, and call 3rd party APIs. Also, the reader has been taught how to write tests. Optionally run the tests from the favorite editor and at the end how to build a deployable JAR file and configure it.

This article has not exhausted all of Duct’s possibilities. There are more things that could be explained in future articles like:

- Communication with a database

- Data validation

- Schedulers

- etc.

Bibliography

[BobCA]: Clean Architecture, Robert C. Martin, Prentice Hall, 2017

[BobCC]: Clean Code, Robert C. Martin, Prentice Hall, 2009

[FowlerPEAA]: Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, Martin Fowler, Addison-Wesley, 2003

[XUnit]: XUnit Test Patterns: Refactoring Test Code, Gerard Meszaros, Addison-Wesley, 2007

The post Building web services with Duct appeared first on Flexiana.

Permalink

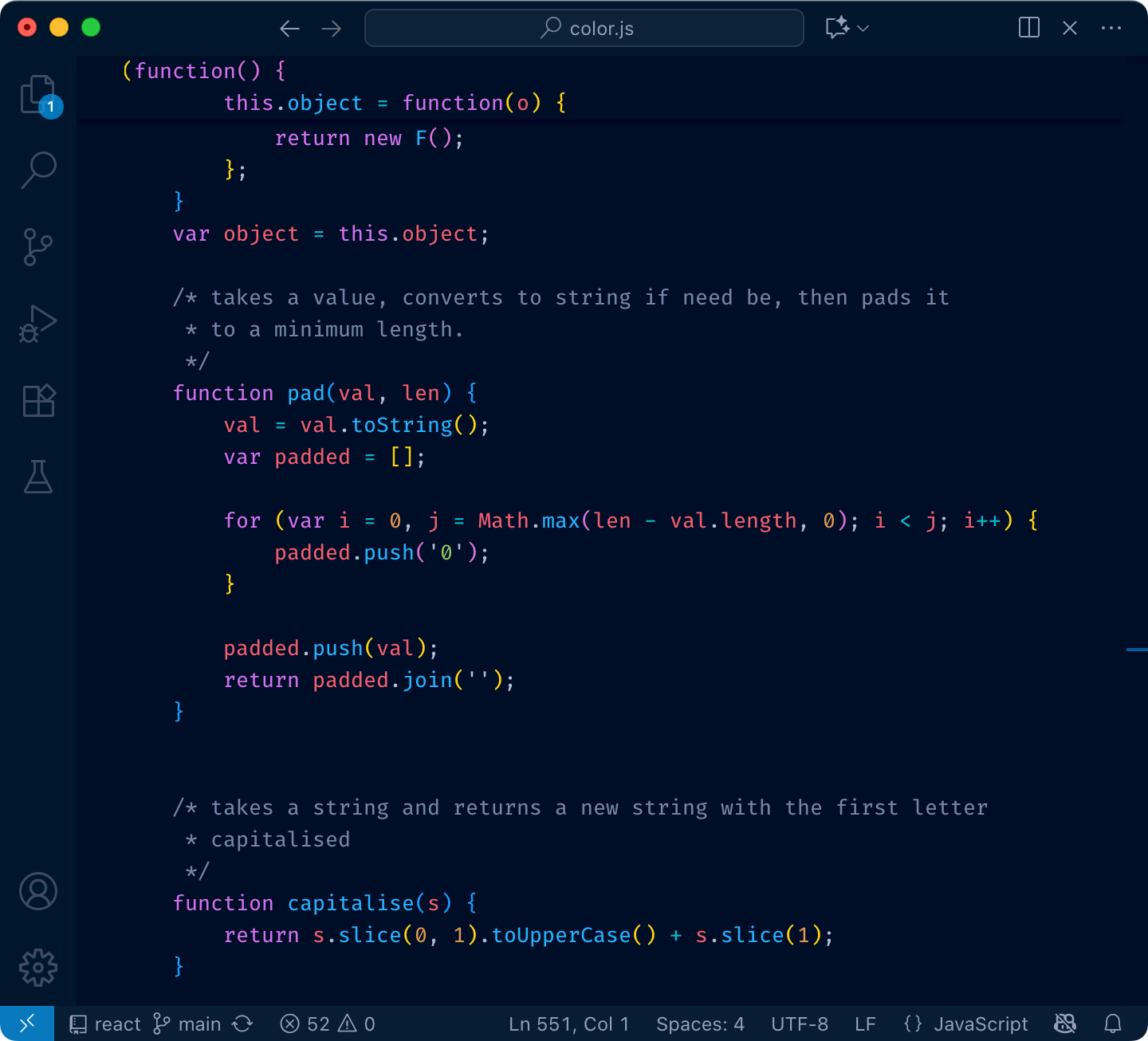

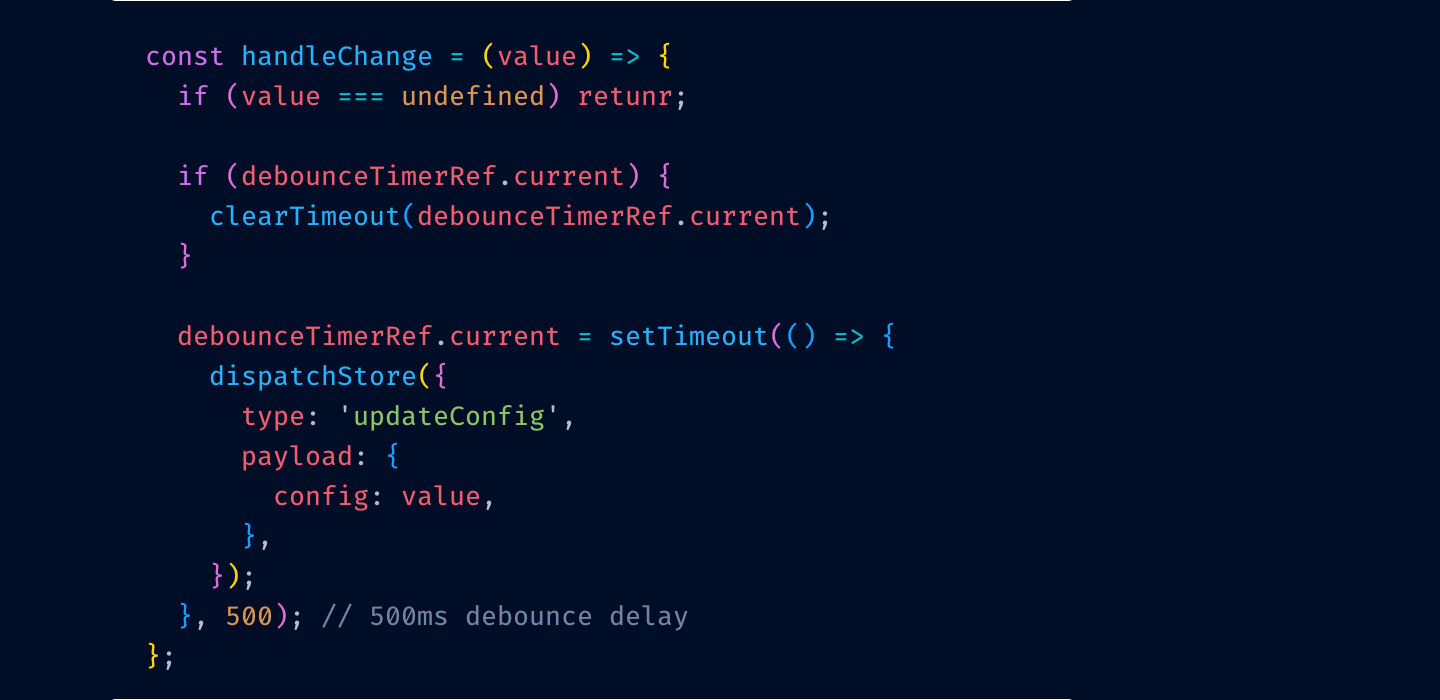

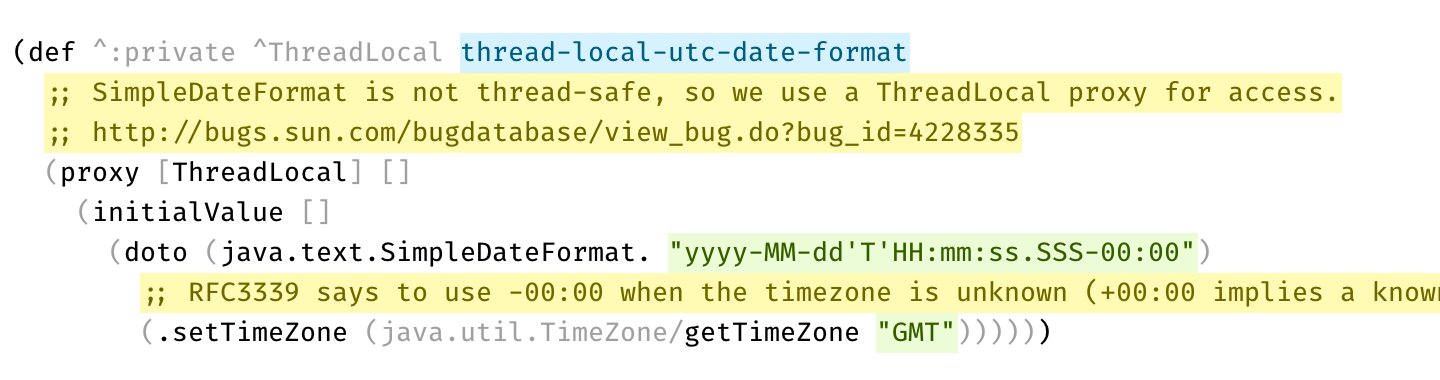

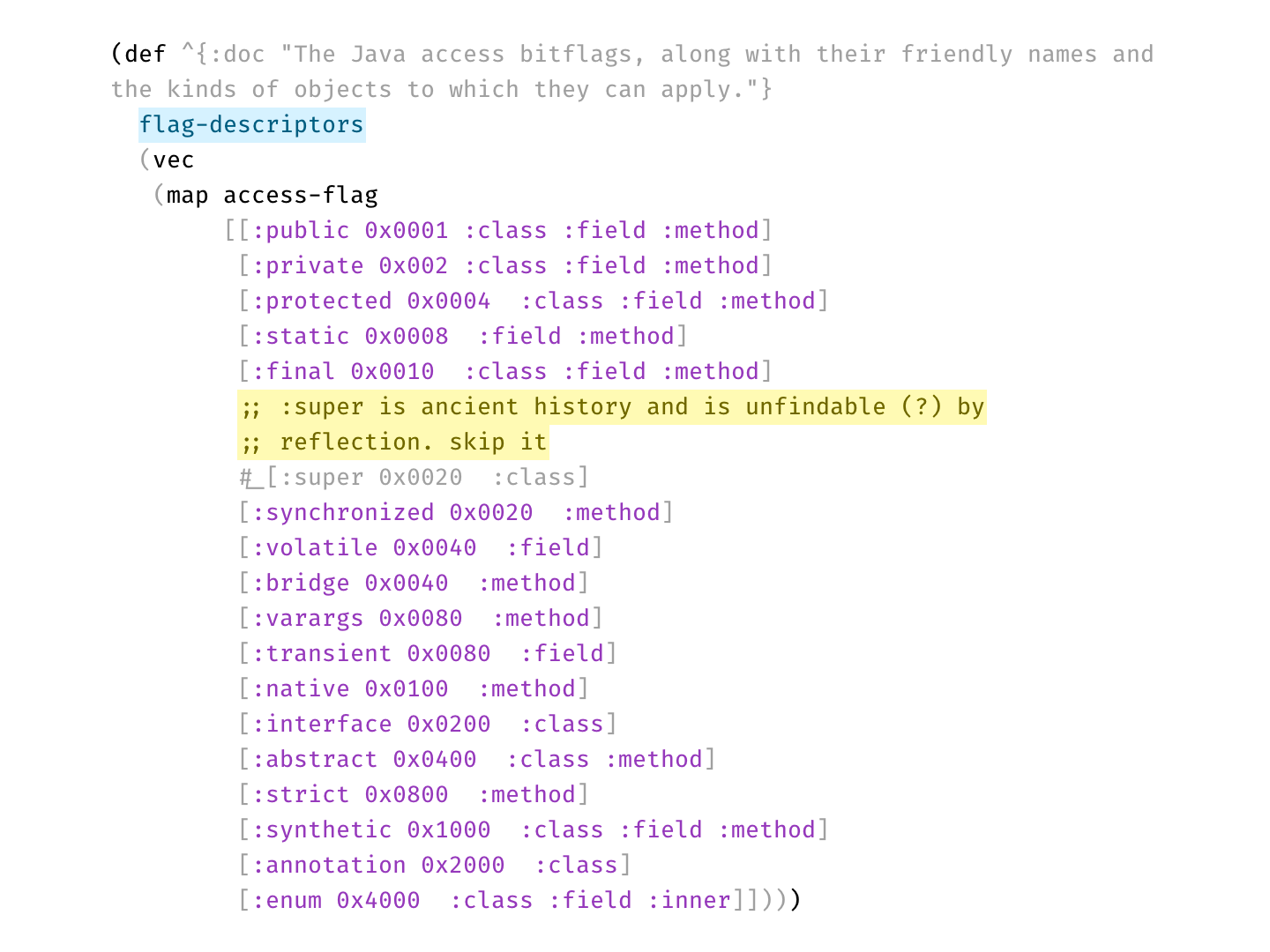

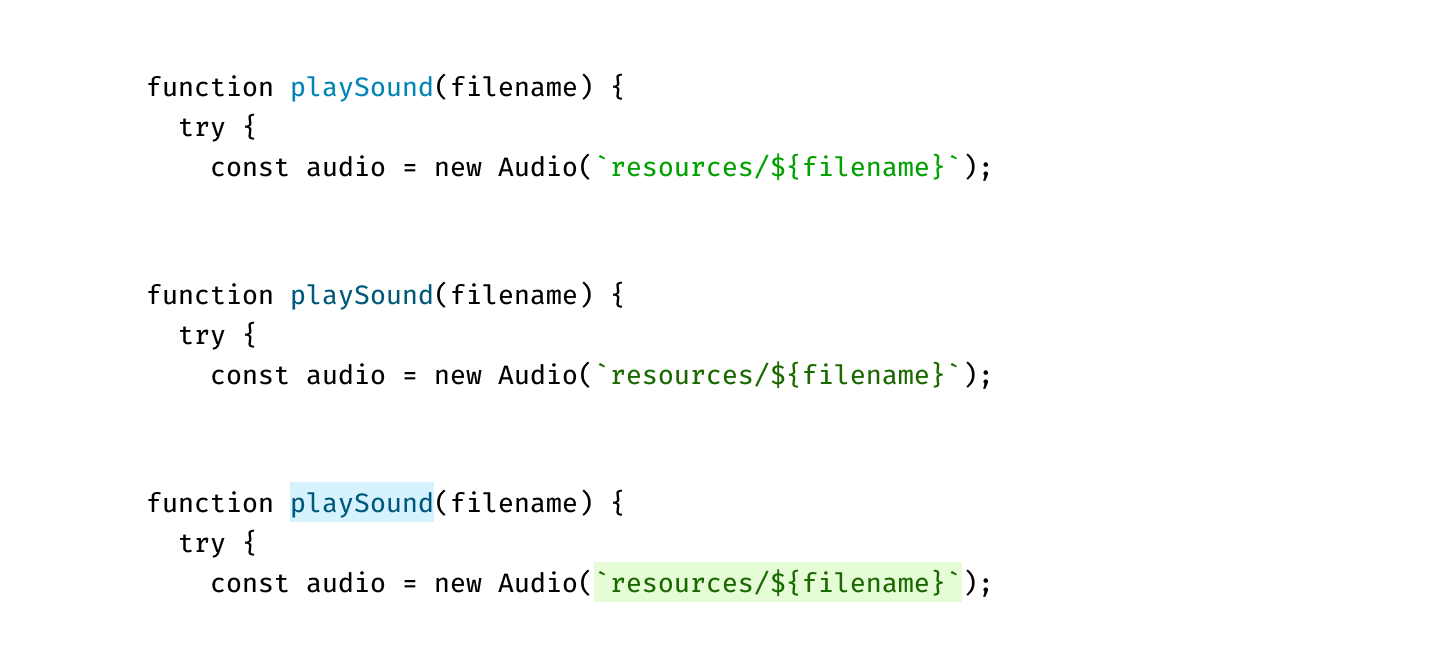

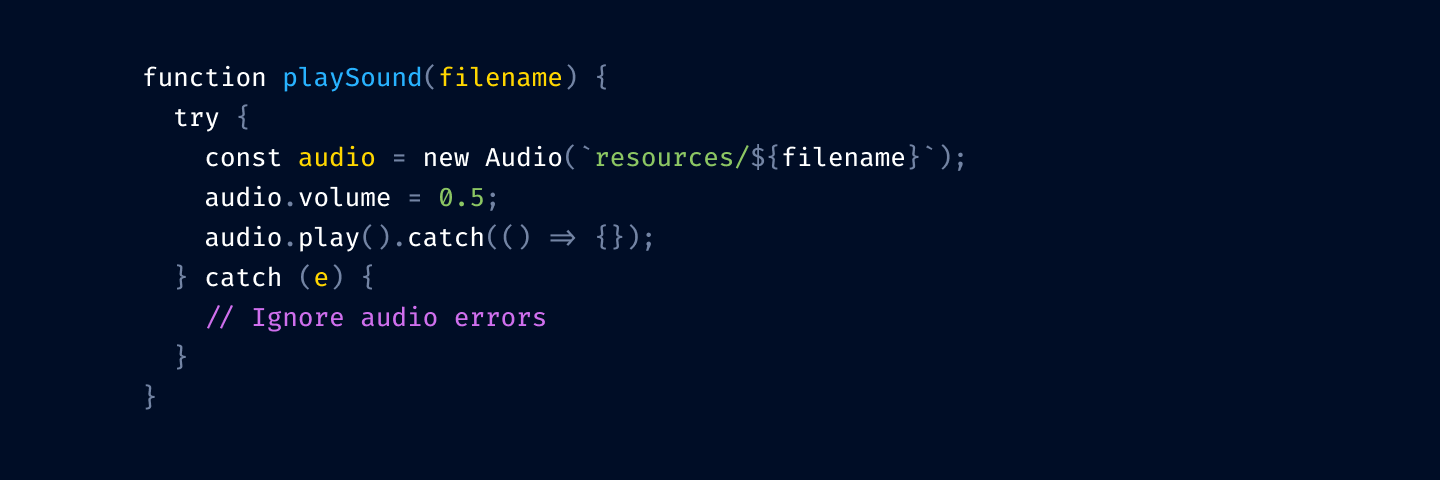

Disabled code is gray, explanation is bright yellow

Disabled code is gray, explanation is bright yellow

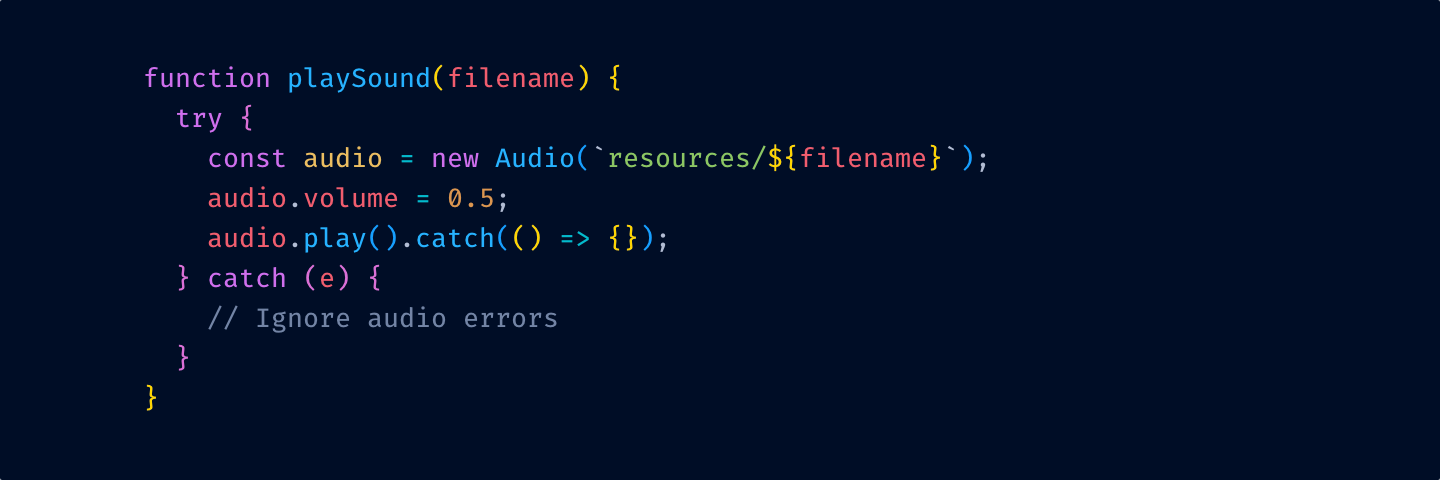

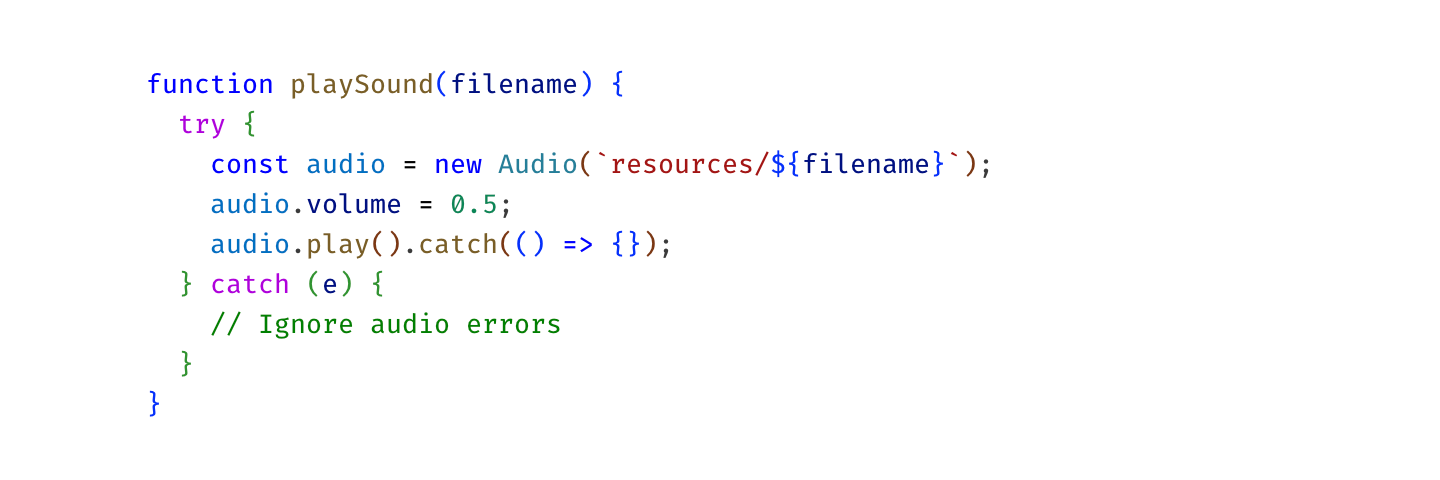

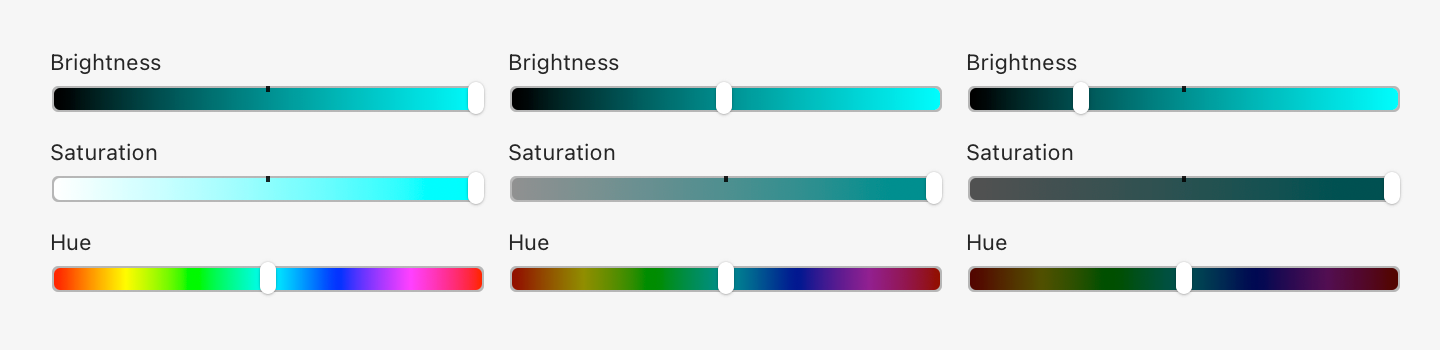

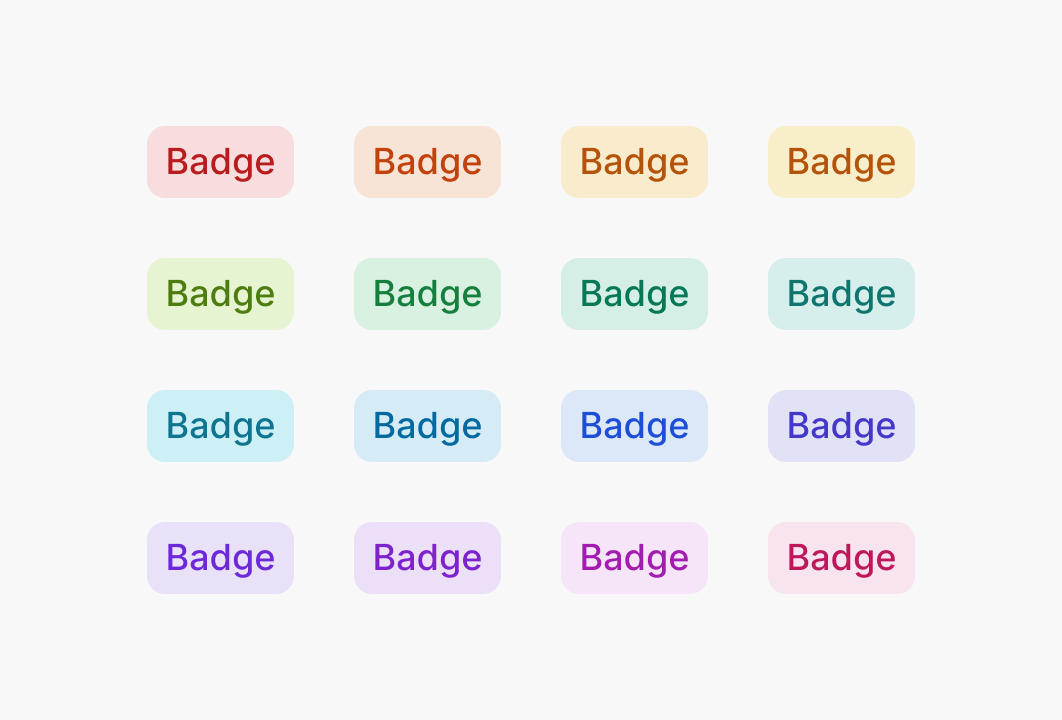

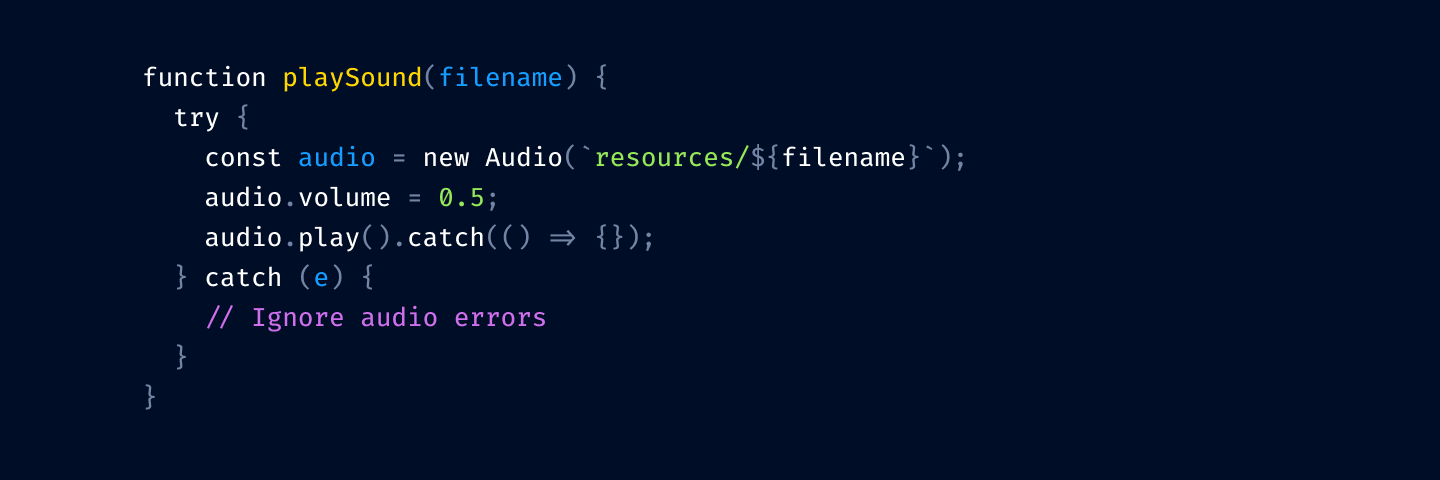

Notice how many colors there are. No one can remember that many.

Notice how many colors there are. No one can remember that many.

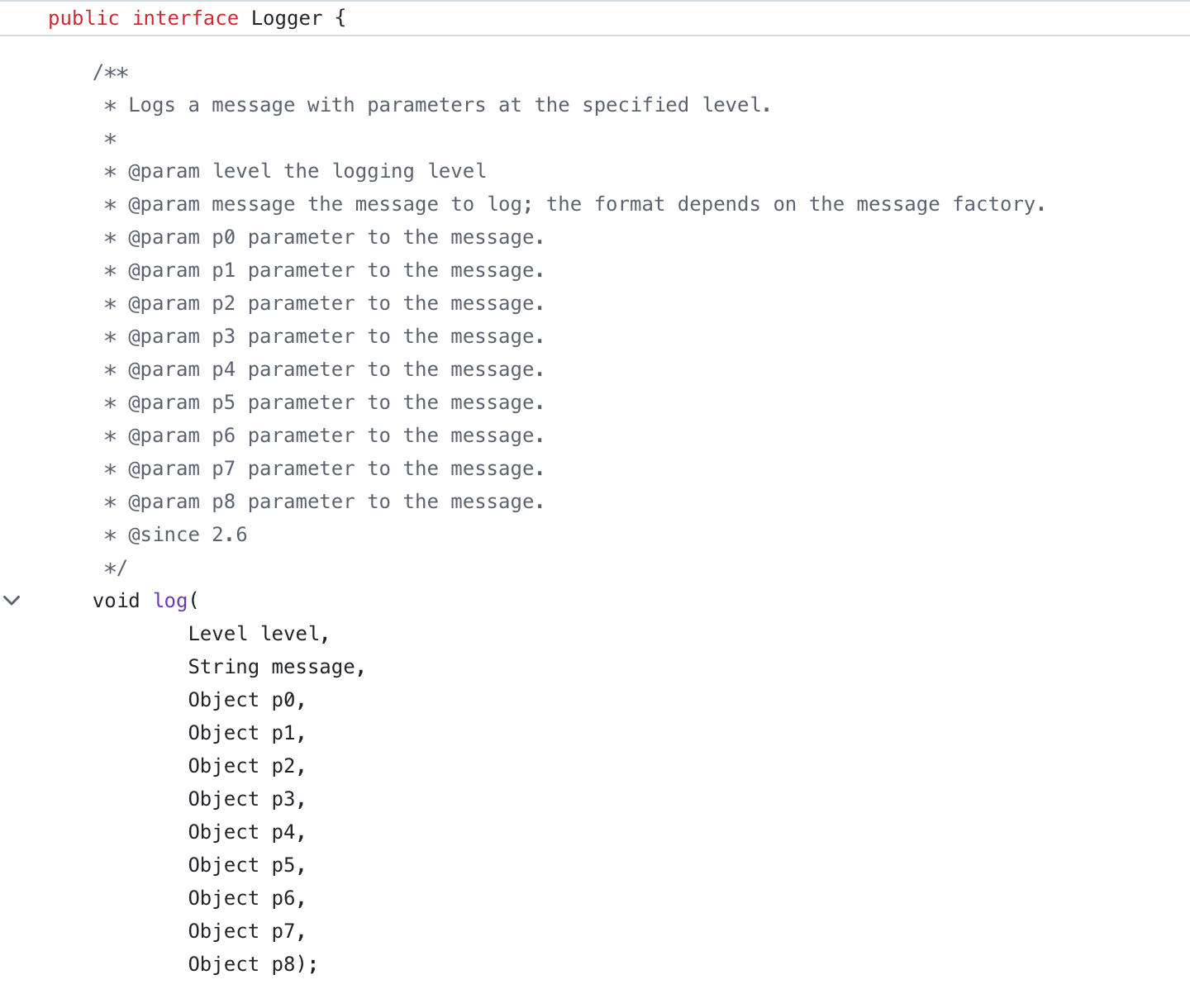

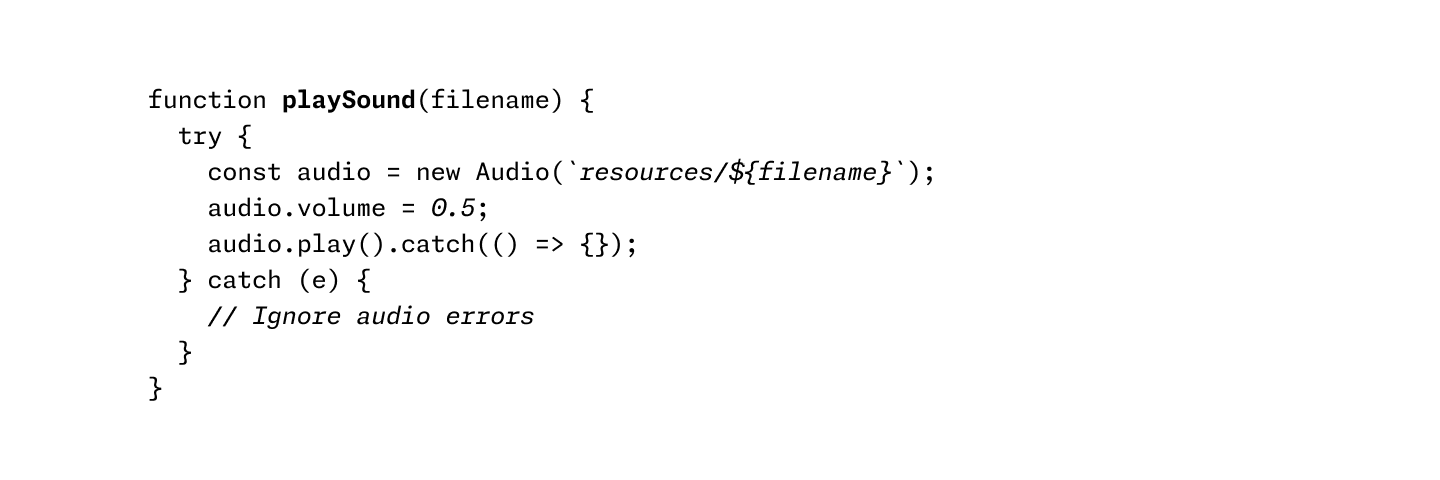

Using italics and bold instead of colors

Using italics and bold instead of colors OkLab l=0.7473 c=0.1253 h=0, 45, 90, 135, 180, 225, 270, 315

OkLab l=0.7473 c=0.1253 h=0, 45, 90, 135, 180, 225, 270, 315

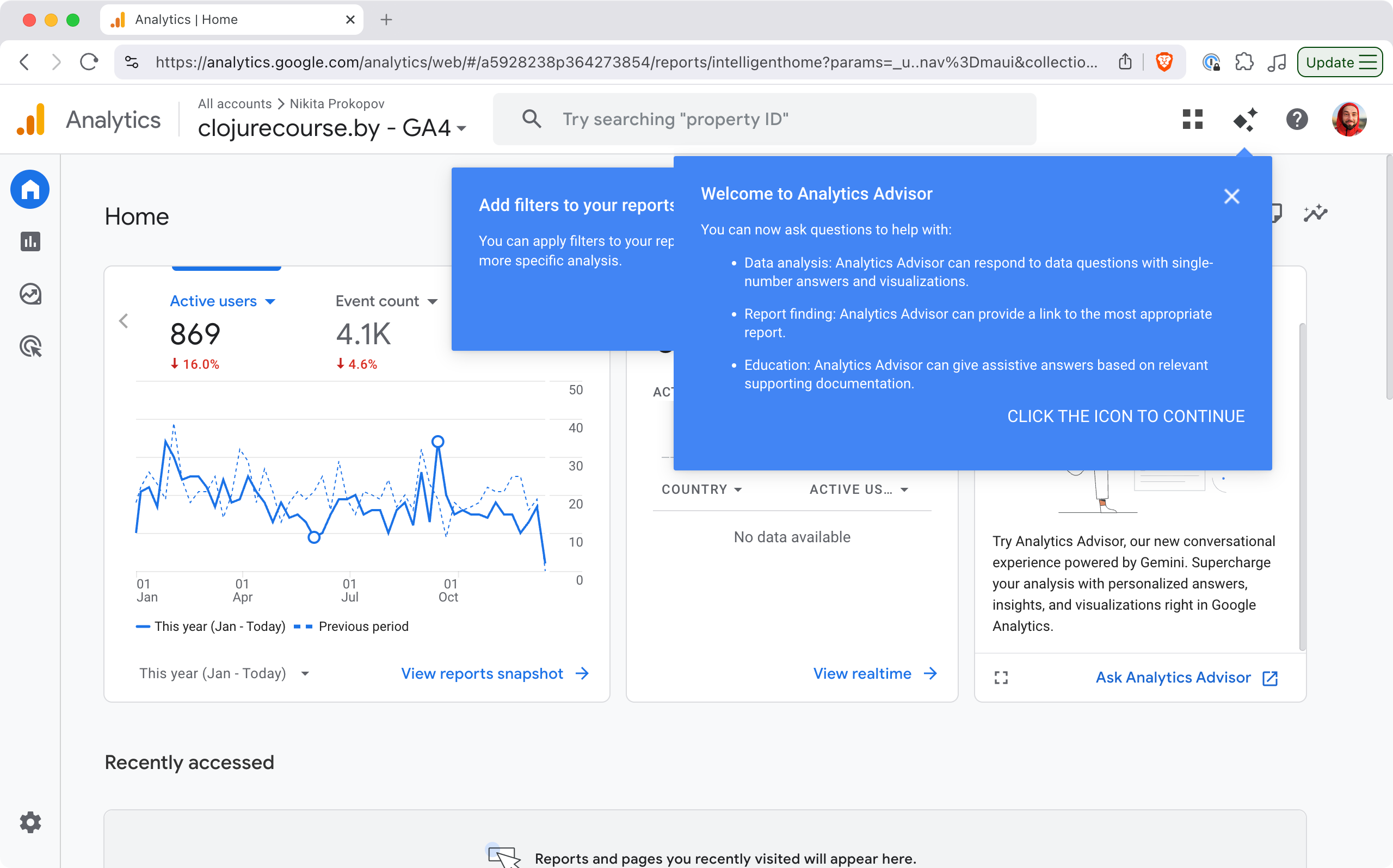

What is going on?

What is going on?